ON THIS PAGE

Early Settlers

The Railroad

Round Hill Incorporated

Businesses, Churches, and Schools

Steps To Protect Genteel Allure

History of Round Hill

by Eugene Scheel

A Waterford historian and mapmaker.

Early Settlers

Thomas sixth Lord Fairfax granted Benjamin Grayson the first tract of land in today's Round Hill in 1731, with Grayson's grant on the west side of Main Street, north of the old railroad. Within a decade Grayson sold the parcel to speculator John Tayloe the younger. The land on the east side of Main Street was granted to William Cox in 1741. In the same year Thomas Gregg was granted today's downtown as part of a fair-sized tract that ran east into Purcellville.

There was no town of Round Hill, however, in any sense of the word, until 1858. The area's leading community was Woodgrove, two miles north of Round Hill, for by 1777 the main road west from Leesburg intersected the present Round Hill-to-Hillsboro Road at Woodgrove. This road did not take the right-of-way of present Route 7 because of the swampy lowlands of the three main branches of the North Fork of Goose Creek which outline the western and eastern approaches to Round Hill.

With the building of the Leesburg and Snicker's Gap Turnpike, today's Route 7, in 1832-1833, the situation changed, and by 1857 Guilford C. Gregg had opened a store at the northwest corner of the pike and the road to Woodgrove. On March 25, 1858, the U.S. postal department opened its Round Hill Post Office, and Gregg was appointed first postmaster, a position he held under the Confederate States of America, and which he was forced to relinquish with the coming of the occupation government, on Sept. 29, 1866. But on Jan. 16, 1868, in the twilight of Andrew Johnson's presidency, there again was a Round Hill postmark, and a less controversial postmaster in the person of William B. Chamblin.

The Railroad

The name goes back to the days Loudoun was a part of Fairfax County, or even earlier. The earliest of the Loudoun County circuit courts, meeting in the spring of 1757, ordered surveyors to mark the best way from Leesburg to the Blue Ridge, and they decided its eastern stretches should stay to the south "of the round hill."

The hill itself is a 910-foot high knob two miles southwest of town. In pre-1722 years its summit was a camping place for Indians traversing the "plain path" - as the Indians called their trails - from the Shenandoah Valley to their main north-south migration route along today's Route 15. The 1722 Treaty of Albany forbade the Indians to migrate east of the Blue Ridge, and thereafter the gentle slopes and summit of the Round Hill became farmland, once again to become a camping and listening place during the Civil War. Shortly, the hill again took its present appearance as farmland, and by the early 20th century it was also called Round Top - to distinguish it from the newly-established town.

The town received its first shot in the arm in May 1875, when the Washington & Ohio railroad came. But dampening the festivities was the loss of a man, killed under an engine turning around on the end-of-the-line roundtable. No longer did the Winchester and Capon Springs stages, that had been running since 1841, at least, ply the dusty pike. With the building of the old Blue Ridge Inn by Bear's Den, south of Snicker's Gap, impromptu stage wagons began the run into Snickersville by the mid-1890's, and the success of the inn prompted the boarding-house craze in Round Hill and the other Loudoun towns along the railroad.

With two or three stores, the proverbial blacksmith and wheelwright shops and livery stables, Round Hill came into its own in 1900, just after the Southern Railroad took over the line.

Round Hill Incorporated

The Southern added trains on weekends, more boarders came, and on Feb. 5, 1900, Virginia's General Assembly incorporated the town of Round Hill, appointing Johnson Taylor, Troy C. Ballenger, and William R. Jones the town commissioners.

Finances, streets, and sanitation were the three main concerns, and each councilman was on two of those committees. Indeed, the first sentence of the Assembly's act creating the town ordered the council to "secure the inhabitants from contagious, infectious, and other dangerous diseases, to regulate the building of stables, privies, and hog pens ...," and the last sentence "to restrain and punish drunkards, vagrants, and street beggars; to prevent vice and immorality; to enforce a proper observance of the Sabbath; to preserve public peace and good order; to prevent and quell riots; disturbances, and disorderly assemblies; to prevent and punish lewd, indecent, and disorderly conduct or exhibitions in said town." Fines up to $50 were specified.

If there were such goings on, the only remembered vice, if one could call it that, was Eppa Hunton - Uncle Ep, the Purcells called him - driving into town. Uncle Ep had a feud with town sergeant Walter Howell, and when Ep drove his two-horse vehicle down from Woodgrove, he'd see Mr. Howell standing on the street, and he'd come out on his horses with a whip, yell at them, and race through town. He'd take the turn on the pike on two wheels, and before Mr. Howell could get on his horse, Ep was outside of the town limits.

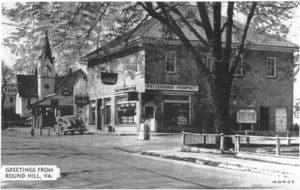

This picture (1880-1900) shows a haywagon on Main Street in downtown Round Hill. Billy Hall's store in on the right, and Paxson-Lodge's Hall is on the left.

The town council's first item of business was to get down to Hamilton to check out the town ordinances. To guard against the Uncle Eps, there was to be no horse-racing - a "trial of speed," they called the sport.

The first crisis came in June 1900 when Mary Pines caught a case of smallpox at her mother's home, and Charles Lloyd was paid a dollar a day to stand guard over the quarantined Sandy Traverse home. As a result, all town property owners were "ordered at once to clean and disinfect all privies, hog pens, and premises generally."

Things got better in 1913, when the town put in a waterworks, and three years later William Birdsall was paid $20 to lease his land on the summit of Scotland Hill, the 877-foot-high hill a mile northwest of town for a reservoir. In 1926 all town privies were to be "updated," and for the first time septic tanks "were encouraged."

Businesses, Churches, and Schools

A rundown of old businesses begins with the boarding houses, and if I miss one or two, kin will have to forgive me, for before autos came in strong in the late 20s, everybody took boarders. They were a bit of Washington, and for Washington, Round Hill was a bit of America.

West Loudoun Street

Beginning at the boardwalk on the west end of town, and on the north side of the pike, was the Lodge House - boarding houses generally took the last name of the operator - run by Henrietta Lodge. Now if you look closely at the end of the present sidewalk - and at the ends of all the present sidewalks - you'll see Walter Howell, our sheriff friend, carved in the walk with the date, 1909. Walter also macadamized the streets - which brought him a nifty $12,000 contract in 1913.

Street names came in early in Round Hill. The town named them, and ordered six street signs to boot, in November 1901. Most of the names - with new signs - are still there. But, Governor Woodrow Wilson would never forgive you; Wilson Street has been renamed South Main Street. Oldtimers, however, called Wilson Street New Cut Road, for the cut through Simpson's Creek dated from about 1890.

The Methodist Church dates from 1889, and in back, where its parsonage stands, stood the first Round Hill public school, a two-roomer built about 1877. Along about 1895 it was enlarged to three rooms, and being frame it went the way of nearly all frame two and three-roomers, burning about 1909.

After the three-roomer, school was held in several vacant rooms about town for a year or two, while Wilmer Baker was busy constructing the eight-roomer that opened in 1911 and also served as Round Hill High School until 1940. Wilmer's handsome building stood on the site of the present school.

The Baptist Church dates from 1905, and before that, dating from the late 1880s at least, was Niels Poulsen's sawmill; his specialty, spokes for vehicles. His raw material came from that vast tract of daytime blackness that was known as Dillon's Woods; it stretched from Purcellville to the Blue Ridge.

Moving east, at today's gas station, was stonemason Clayton L. Everhart's marble and granite works. The stone came in by rail, was buggied to the works, and C.L., as he was called, etched the stones freehand, designing the lambs, urns, and lilys that grace most churchyards in western Loudoun.

On the northwest corner of the pike and Main Street - usually called the Woodgrove Road - was Niels Poulsen's house and a big vegetable garden. In 1926, Dr. Patterson had Clarence Kelley build the present stuccoed pyramid-roofed building, and downstairs until 1966 Dr. Patterson had his pharmacy. There were also assorted stores in the building, the town office, and upstairs a dance hall and theater, and George Lee would come in from Purcellville to cut your hair.

Main Street

North on Main Street, at the present firehouse was William Alexander "Alex" Lynch's livery stable, the town's largest. Alex owned the town hearse, and he and son John often carried the mail in pre-auto days. Henderson Tracy was the other regular carrier. Alex was in business long before the century's turn, and by the teens his son had taken over. The auto and the Depression were his undoing, in the early 30s.

Hayward Thompson's still-standing store was built in 1901, and he ran it until 1922. To beat the competition he'd often get up a four and five in the morning so he would be open for the farmers who brought their milk to the train.

Steps To Protect Genteel Allure

A hundred Junes ago, the newly elected Round Hill Town Council and its mayor, George T. Ford, met for the first time to draft a set of ordinances that were the strictest I've seen. A crisis had arisen in the business community, for in 1899 the Southern Railway began extending its tracks westward to Snickersville, just four miles distant, at the base of the Blue Ridge Mountains. The railroad's terminus since 1875 had been the village of Round Hill, and its boarding houses, merchants and livery stables had profited from the summertime dollars of well-to-do Washingtonians and diplomats, many of whom spent their summers in Loudoun to escape the heat, humidity and threat of disease.

The first train into Snickersville arrived on schedule July 4, 1900, and Southern Railway began lobbying Loudoun officials to change the town's locally revered name, in use since 1830, to a more alluring "Bluemont."

A main reason for Southern's extension was the construction in 1893 of the Blue Ridge Inn, atop the ridge near a scenic rock outcrop called Bear's Den, overlooking the Shenandoah Valley. The inn's chef, Jules DeMonet, had been chef at the White House. By 1900, the inn was fast becoming the area's premier summer vacation spot. The half-hour wagon ride up the scenic mountain from Bluemont--as Snickersville became in September of that year--was far better than the five-mile, 1 1/2-hour jaunt from the Round Hill station because, often, the flats along the old Snickers Gap Turnpike (now Route 7) were soggy or flooded, and wagons got mired.

So Round Hill officials incorporated in January 1900 to spruce up the town's image and try to retain its summer clientele as well as its decades-old position as Loudoun's leading town of the far west.

Some Round Hill residents recalled that another transportation improvement, the Snickers Gap Turnpike (Snickersville Turnpike), had given their village its start—and had begun the demise of Woodgrove, 1 1/2 miles north of Round Hill, on the older main road west.

The June 1900 ordinances were enacted to ensure that Round Hill would not become another Woodgrove and began by prohibiting residents from removing "dirt, sand or rock" from town streets and alleys. They also mandated the removal of all "obstructions" from public ways, especially "hitched horses so as to obstruct sidewalks." The main sidewalk, a wooden boardwalk, ran along the north side of the turnpike, named Loudoun Street in 1901.

Here the summer people paraded, especially on Sundays, watched by locals who wanted to see the latest in Washington finery. Predictably, the town's three churches for whites arose by the boardwalk: the Methodist Church in 1889 (it had moved from Woodgrove), Mount Calvary Episcopal in 1892 and the Baptist Church in 1905.

The main boarding houses also were along the boardwalk or across the street: Henrietta Lodge's, at the west end of town where the boardwalk began; Madeline and Annie Kuhlmann's across the street; and Flora Katherine Hammerly's at the northeast corner of Locust. At the Kuhlmann House, summer guest Lloyd C. Douglas wrote his best-selling biblical novel, "The Robe." The typical rate was $7 a week room and board, plus $1.50 for Sunday dinner. The guests' favorite sport was lawn croquet. At BridgeStreet, the boardwalk ended.

Safety was another concern, and one of the ordinances prohibited "any attempt at trial of speed between two or more horses or mules" on any street. Addie Purcell told me the story of her Uncle Ep--Eppa Hunton--who would drive his two-horse vehicle down from Woodgrove. When he saw Walter Howell, town sergeant, Ep would lay the whip on his horses, and they'd race through town, taking the turn into the pike on two wheels. Before Howell could mount his horse, Ep was beyond the town limits.

Howell later went out on his own and in 1909 replaced the boardwalk and board sidewalks with cement walks. At the end of each walk, he inscribed his name and the year. You still can see the writing.

About that time, automobile drivers began to venture into the hinterlands, and in July 1915, the Town Council decreed that the speed limit should be 12 miles an hour. Violators were subject to the steepest town fines, $25, or three days in jail. Previously, fines had ranged from $1 to $20--and those were days when the average person made $1 a day.

Two townsmen at that time owned autos. The first was a Ford runabout bought by physician Ed Copeland about 1910. Jimmy Carruthers bought the second, an E-M-F, a few years later. Named for its manufacturer, Edward M. Flanders, the E-M-F was a popular early auto in Piedmont Virginia. It had two nicknames, "Every Mechanical Fault" and "Every Morning Fix."

To make summer folk feel at home in the evening, the town had six street lights, lit with coal oil (a primitive kerosene) by lamplighter S.E. Hindman. Though businesses and homes had electric lights by late 1912--courtesy of the newly electrified Washington & Old Dominion Railroad, the successor to the Southern Railway that year--street lamps still used coal oil. Some residents still can recall little Martha Howell pulling her red wagon, laden with the five-gallon oil cans, followingher father, Austin, the second lamplighter. As a teenager, Martha took over the job until electric street lights came on Jan. 1, 1921.

For the further benefit of summer boarders, ordinances were enacted "to restrain and punish street drunkards, vagrants and street beggars; to prevent vice and immorality; and to enforce a proper observance of the sabbath." Specifically, there was to be no congregating anywhere, and "loud or boisterous talking or to insult or to make rude and obscene remarks."

In 1912, town minutes noted that "Councilman [Landon] Hammerly reported a man and woman being together who were not married and from previous reports it was deemed best by the council that they be notified to marry or leave the Corporation." Subsequent minutes do not record the outcome.

Blacks were not welcome in the corporation, although some ex-slaves had lived within the new town limits since the 1870s. Indeed, Round Hill's first church was their Mount Zion, built in 1881. As was the custom in most small Virginia towns, blacks were to live outside the town limits--but close enough to supply labor to whites in town.

The Negro section near Round Hill was called The Hook. At its center, Bridge Street, the first road south, hooked westward. Each Sunday, blacks in their finery entered town en masse on their way to Mount Zion. Whites entered The Hook only to gaze upon Mount Zion baptisms, held by the plank-and-truss bridge that spanned the west branch of North Fork.

Several ordinances were drafted to promote health, suggested by physician James Edward Copeland, who had come to Round Hill in 1887 after a seven-year practice in Rectortown in Fauquier County.

Copeland was one of the first area physicians to believe in isolating a patient with a contagious disease. When Mary Pines caught smallpox in June 1900, she and seven others who had been in contact with her were ordered to "remain in quarantine" in her mother's house "until released by propper authorities." A guard, paid $1 a day, saw to it that no one entered or left. Then, 11 property owners were "ordered at once to clean and disinfect all privies, hog pens and premises generally."

Cholera, influenza and typhoid fever also prompted quarantines. Typhoid, caused by contaminated drinking water, was rampant during those years, and Round Hill relied on a strong spring with pure water. Its stone base still can be seen, a few hundred yards west of the town limits, by the old railway right of way.

But with a population that grew from 318 in 1900 to 379 in 1910, a stronger water source was needed, and by the summer of 1913, potable water was supplied by iron pipes from a spring-fed reservoir on Scotland Hill.

Other health ordinances prohibited horses, hogs and female dogs "while in heat" from running loose. Cows could stray about between 6 a.m. and 7 p.m. but were to be penned at night.

Mayor Ford was responsible for carrying out the town ordinances. He came to Round Hill from Page County in 1877 when he was 24, and the store he opened is now the town office. In 1901, he ran for the state Senate and served two terms representing Loudoun and Fauquier.

"Honest George Ford," was his sobriquet, as illustrated by the time young Albert Purcell brought some aged chickens into Ford's store for resale. The clerk gave him the correct price for older chickens, not the price for young fryers. But when Ford sold them in Washington, he got the fryer price and handed Albert the extra change.

Copyright © Eugene Scheel